En passant

- This article uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves.

En passant (from French: in passing) is a move in the board game of chess. En passant is a special capture made immediately after a player moves a pawn two squares forward from its starting position, and an opposing pawn could have captured it as if it had moved only one square forward. In this situation, the opposing pawn may capture the pawn as if taking it "as it passes" through the first square. The resulting position is the same as if the pawn had only moved one square forward and the opposing pawn had captured normally. The en passant capture must be done on the very next turn, or the right to do so is lost.[1] Such a move is the only occasion in chess in which a piece captures but does not move to the square of the captured piece (Burgess 2000:463). If an en passant capture is the only legal move available, it must be made. En passant capture is a common theme in chess compositions.

This rule was added in the 15th century when the rule giving pawns the option of initially moving two squares was introduced. The rationale is so that a pawn cannot pass by another pawn using the two-square move without the risk of it being captured.

Contents |

The rule

If a pawn on its original square moves two squares and there is an opposing pawn on its fifth rank on an adjacent file, the opposing pawn may capture it as if it had moved only one square. The conditions are:

- the pawn making the en passant capture must be on its fifth rank

- an opposing pawn on an adjacent file must move two squares from its initial position in a single move

- the pawn can be captured as if it moved only one square

- the capture can only be made at its first opportunity.

|

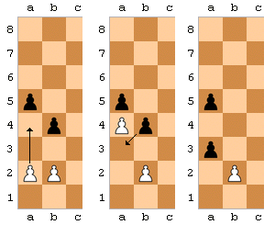

Black to move

The black pawn is in its initial location. If it moves to f6 (marked by ×), the white pawn could capture it.

|

White to move

Black moved his pawn forward two squares from f7 to f5, "passing" f6.

|

Black to move

On the next move, White captures en passant, capturing the pawn as if it had moved to f6.

|

Historical context

Allowing the en passant capture is one of the last major rule changes in European chess that occurred between 1200 and 1600, together with the introduction of the two-square first move for pawns, castling, and the unlimited range for queens and bishops (Davidson 1949:14,16,57). Spanish master Ruy López de Segura gives the rule in his 1561 book Libro de la invencion liberal y arte del juego del axedrez (Golombek 1977:108). In most places the en passant rule was adopted as soon as the rule allowing the pawn to move two squares on its first move but it was not universally accepted until the Italian rules were changed in 1880 (Hooper & Whyld 1992:124–25).

The motivation for en passant was to prevent the newly-added two-square first move for pawns from allowing a pawn to evade capture by an enemy pawn. Specifically, the rule allows a pawn on a player's fifth rank the opportunity to capture the opponent's pawn on an adjacent file that advances two squares from its starting square as though it had only moved one square (Davidson 1949:16). Asian chess variants, because of their separation from European chess prior to that period, do not feature any of these moves.

Notation

In either algebraic or descriptive chess notation, en passant captures are sometimes denoted by "e.p." or similar, but such notation is not required. In algebraic notation, the move is written as if the captured pawn just advanced only one square, e.g., bxa3 (or bxa3 e.p.) in this example (Golombek 1977:216).

Threefold repetition and stalemate

The possibility of an en passant capture has an effect on claiming a draw by threefold repetition. Two positions whose pieces are all on the same squares, with the same player to move, are considered different if there was an opportunity to make an en passant capture in the first position, because that opportunity by definition no longer exists the second time the same configuration of pieces occurs (Schiller 2003:27).

In his book about chess organization and rules, International Arbiter Kenneth Harkness wrote that it is frequently asked if an en passant capture must be made if it is the only move to get out of stalemate (Harkness 1967:49). This point was debated in the 19th century, with some arguing that the right to make an en passant capture is a "privilege" that one cannot be compelled to exercise. In his 1860 book Chess Praxis, Howard Staunton wrote that the en passant capture is mandatory in that instance. The rules of chess were amended to make this clear (Winter 1999). Today, it is settled that the player must make that move (or resign). The same is true if an en passant capture is the only move to get out of check (Harkness 1967:49).

Examples

In the opening

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

There are some examples of en passant in chess openings. In this line from Petrov's Defence, White can capture the pawn on d5 en passant on his sixth move.

- 1. e4 e5

- 2. Nf3 Nf6

- 3. d4 exd4

- 4. e5 Ne4

- 5. Qxd4 d5 (diagram)

- 6. exd6 (Hooper & Whyld 1992:124–25).

Another example occurs in the French Defense after 1.e4 e6 2.e5, a move once advocated by Wilhelm Steinitz (Minev 1998:2). If Black responds with 2...d5, White can capture the pawn en passant with 3.exd6. Likewise, White can answer 2...f5 with 3.exf6.

Unusual examples

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black has just moved his pawn from f7 to f5 in this game between Gunnar Gundersen and Albert H. Faul.[2] White could capture the f-pawn en passant with his e-pawn, but had a different idea:

- 13. h5+ Kh6

- 14. Nxe6+ g5 Note that the bishop on C1 actually affects the check on the king

- 15. hxg6 e.p. #

The en passant capture places Black in double check from White's rook on h1 and bishop on c1. Since Black cannot parry both checks at once, and his last route of escape, moving to g7, is blocked by White's knight at e6, he is checkmated.

The largest known number of en passant captures in one game is three, shared by three games; in none of them were all three captures by the same player. The earliest known example is a 1980 game between Alexandru Sorin Segal and Karl Heinz Podzielny (Winter 2006:98–99).[3]

In chess compositions

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

En passant captures have often been used as a theme in chess compositions, as they "produce striking effects in the opening and closing of lines." (Howard 1961:106). In the 1938 composition by Kenneth S. Howard, the first move 1.d4 introduces the threat of 2.d5+ cxd5 3.Bxd5#. Black may capture the d4 pawn en passant in either of two ways:

-

- The capture 1...exd3 e.p. shifts the e4 pawn from the e- to the d-file, preventing an en passant capture after White plays 2.f4. To stop the threatened mate (3.f5#), Black may advance 2...f5, but this allows White to play 3.exf6 e.p. with checkmate due to the decisive e-file opening.

- If Black plays 1...cxd3 e.p., White exploits the newly-opened a2-g8 diagonal with 2.Qa2+ d5 3.cxd6 e.p.#.

See also

- Pawn (chess)

- Rules of chess

Notes

- ↑ FIDE rules (En Passant is rule 3.7, part d)

- ↑ Gundersen vs. Faul. ChessGames.com. Retrieved on 2009-06-12.

- ↑ A. Segal vs. K. Podzielny, Dortmund 1980. Published by 365Chess.com. Retrieved on 2009-12-05.

References

- Burgess, Graham (2000), The Mammoth Book of Chess (2nd ed.), Carroll & Graf, ISBN 978-0-7867-0725-6

- Davidson, Henry (1949), A Short History of Chess, McKay, ISBN 0-679-14550-8 (1981 paperback)

- Golombek, Harry (1977), Golombek's Encyclopedia of Chess, Crown Publishing, ISBN 0-517-53146-1

- Harkness, Kenneth (1967), Official Chess Handbook, McKay, ISBN 1114157031

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-866164-9

- Howard, Kenneth S. (1961), How to Solve Chess Problems (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0486207483, http://books.google.com/?id=TAr0VrN-G3MC&lpg=PA106&dq=%22en%20passant%22%20chess&pg=PA106#v=onepage&q=%22en%20passant%22%20chess, retrieved 2009-11-30

- Just, Tim; Burg, Daniel B. (2003), U.S. Chess Federation's Official Rules of Chess (5th ed.), McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3559-4

- Minev, Nikolay (1998), The French Defense 2: New and Forgotten Ideas, Thinkers' Press, ISBN 0-938650-92-0

- Schiller, Eric (2003), Official Rules of Chess (2nd ed.), Cardoza, ISBN 978-1-58042-092-1

- Sunnucks, Anne (1970), The Encyclopaedia of Chess, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0709146971

- Winter, Edward (1999), Stalemate, Chesshistory.com, http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/stalemate.html, retrieved 2009-06-12

- Winter, Edward (2006), Chess Facts and Fables, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-2310-2